Ken Burns on how his film ‘The American Revolutio’ took longer to make than the war itself

After making films for more than half a century, Ken Burns has become an institution as much as a documentarian. The 72-year-old’s latest film for PBS, “The American Revolution,” is a six-part, 12-hour-long series chronicling a war Burns calls “more of a civil war than our Civil War.” From all the subjects he’s covered — the Vietnam War, baseball, World War II, jazz, the Prohibition period, Jack Johnson, and so many more — Burns says his latest is “foundational.”

Before embarking on this project, Burns and his team of co-directors (Sarah Botstein and David Schmidt) and screenwriter Geoffrey C. Ward spent a decade interviewing leading scholars, scouring historical materials, and researching thousands of books. Burns assembled a cast that he believes might be the greatest ever assembled for any film project: Tom Hanks, Meryl Streep, Morgan Freeman, Laura Linney, Claire Danes, Kenneth Branagh, Jeff Daniels, Samuel L. Jackson, Edward Norton, and Liev Schreiber, among a raft of other A-list talent.

The innovative and dazzling cartography used in bringing the dimension and scale of “The American Revolution” to life required more maps being used in this film than all his previous work combined. Burns’ work on “The American Revolution” spanned the presidencies of Obama, Trump, Biden, and Trump’s second term. Throughout the 12 hours, far from the turbulent material feeling anachronistic, the present-day parallels are almost disturbingly constant and numerous.

Depth Perception speaks with Ken Burns about the process of creating his latest project for over a decade and why cataloging the past is critical for understanding the present. —Brin-Jonathan Butler

Learn from top longform journalists and find the best in-depth reporting. Subscribe to Depth Perception:

About nine hours into your new series, “The American Revolution” plowed into where I live in Connecticut. The Battle of Norwalk —

If we can even call it a battle (laughs). The British basically attacked and burned down Norwalk, along with Fairfield and New Haven, I think.

This is why I thought you might find the point interesting. About a mile from where I live, my mother-in-law grew up on Strawberry Hill Avenue, in a house built in 1705. Her basement was connected to the underground railroad. But in 1779, General Tryon and his troops were burning down nearly all of East Norwalk. The only reason my mother-in-law’s home still stands is because, from the upstairs window of the house, a hopping mad wife was repelling British troops on her own with a shotgun while her husband was out fighting them with a militia. It’s one of the only houses in the neighborhood that remains from that time.

The Revolutionary War is the story of us, right? It’s the story of a divided America — always has been. In some ways our revolution is more of a civil war than our Civil War was.

You’ve said of this film that you won’t work on a more important film. Can you elaborate on what makes you say that?

It’s actually been misquoted. It’s slightly different from what you said and I think you’ll immediately make the distinction. I said first about our film on the Holocaust, which came out in 2022, that I won’t work on a more important film. I told it to the world and I meant it. But the important word is more. I hope that there have been five or six films, you know, about the Civil War, baseball, jazz, Roosevelt, World War II, Vietnam — which are as important.

This current film was our origin story and we kind of make it bloodless and gallant and superficial. We focus on really good things — guys in Philadelphia thinking great thoughts. That’s a really huge part of it, but it’s not the only part.

What were some of the biggest surprises that came up during the decade that you worked on this project?

Every single day. Every day it was like everything stood out and nothing. Everything was a surprise. I mean, that’s what happened. The response since it was first broadcast and streamed in mid-November has been, “Wow. I had no idea.” And I think that’s because for the last 10 years, I had been going, “Wow. I had no idea.”

A lot of it has to do with the violence. This was a revolution and a very bloody one. It is also a very bloody civil war. And it’s also a global war that has a lot of partners involved in it.

In my editing room, we have a neon sign that says, “It’s complicated.” Human events are complicated. It’s important to find out new and destabilizing information. Facts outweigh story and artistic considerations. We’ve always rolled that way.

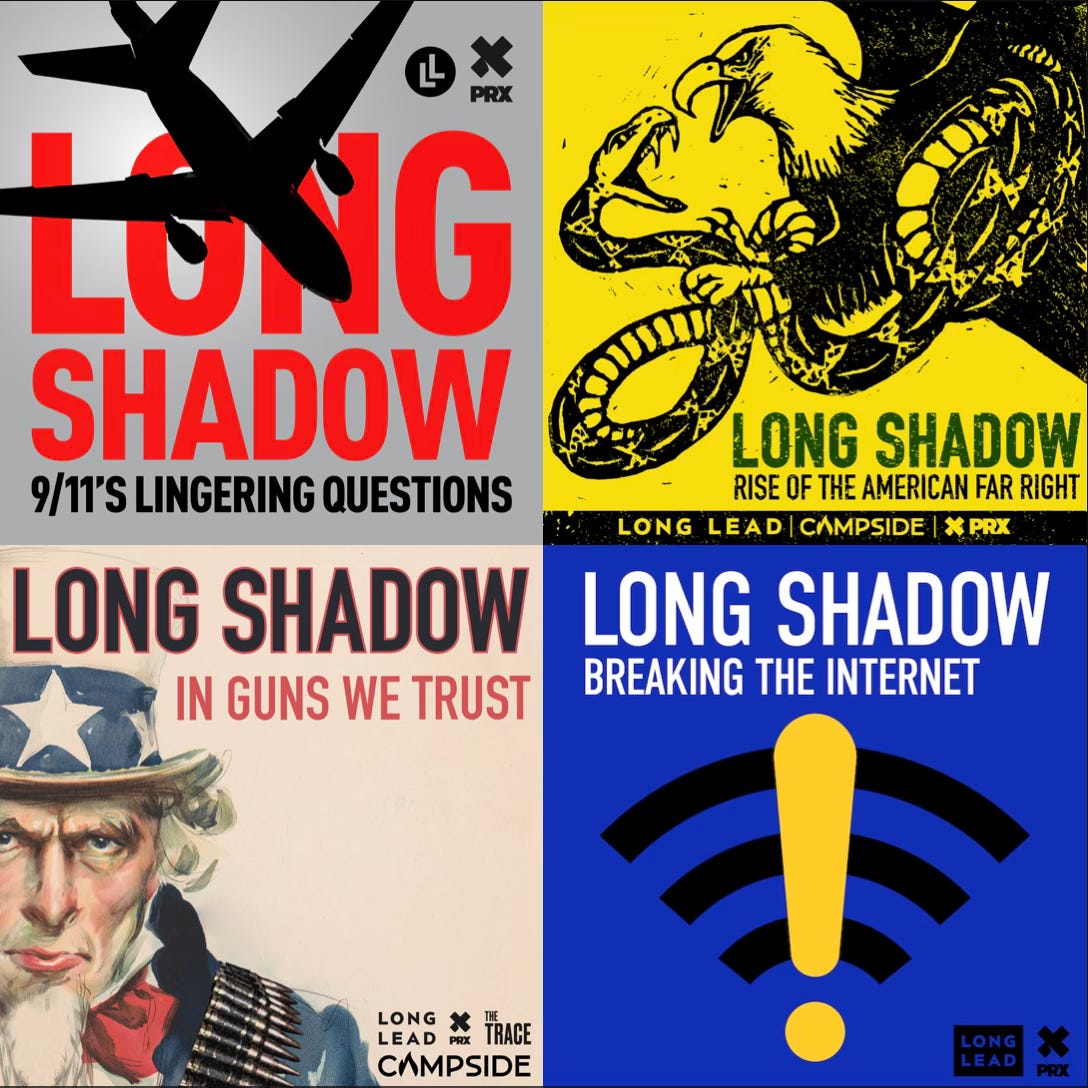

Listen to the “Long Shadow” of American history

Through a series of riveting, complex narratives, Long Lead’s podcast Long Shadow makes sense of what people know — and what they thought they knew — about the most pivotal moments in U.S. history, including Waco, Columbine, Y2K, 9/11, COVID-19, January 6, and beyond.

Hosted by Pulitzer-finalist historian, author, and journalist Garrett Graff, this Peabody-nominated podcast has been called “rigorous, authoritative, and an electrifying listen” by the Financial Times and honored as one of the year’s best podcasts by The Atlantic, Audible, Mashable, Rolling Stone, and The Week.

A winner of the Edward R. Murrow Award and the RFK Human Rights Journalism Award, Long Shadow has also been honored with eight Signal Awards, including for Best History, Best Documentary, Best Technology, and Best Activism, Public Service, & Social Impact Podcast. The podcast’s second season has been added to the history program at the University of Houston and the third season has been integrated into Harvard Law School’s curriculum on the Second Amendment.

Looking for another revolution? Listen to Long Shadow wherever you get your podcasts.

Encountering George Washington mandating vaccines for his troops and many other moments from the war that echo with friction in today’s cultural and political landscape in America, I wondered how you sought to handle presenting them?

We’re never explicit. In fact, we have a law against that. I’ve taken stuff out because if I left them in, you wouldn’t believe me that I didn’t.

Mark Twain was supposed to have said that history doesn’t repeat itself. Which, of course, it doesn’t. No event has happened twice, he said, but it rhymes. I’ve spent my entire professional life seeing those rhymes.

In this series there’s an invasion of Canada. There’s a continent-wide pandemic that kills more people than the revolution. There is a debate over inoculation. There is just rhyme after rhyme after rhyme. But this is human nature. These things occur and reoccur continually and our job is to not build neon signs with big arrows that demand you to look at how much it reminds you of today.

You’ve called the cast of actors you assembled for “The American Revolution” one of the best casts there’s ever been for a film.

“The Longest Day”’s cast had every major male actor in Britain, Germany, America, and France, right? I think our film is longer. We didn’t have any photographs, obviously. No newsreels. Out of necessity — all of my films, thanks to PBS, are essentially director’s cuts.

I wrote an article about a woman who stole — her word — J.D. Salinger’s voice on a recorder. Betty Eppes went to Cornish, New Hampshire and interviewed Salinger in 1980 as a journalist looking for an interview. She secretly recorded him. Since Salinger died in 2010, there has never been a recording of his voice produced to the public. Eppes told me she was offered over $500,000 to sell the tape by a wealthy business man. So my question for you is, what is the actual value for people to know how George Washington or Thomas Jefferson or Ben Franklin actually sounded?

Let’s start with Abraham Lincoln. Because we know a lot about how he sounded and it’s thin and reedy and it’s nasally. He could reach people without amplification. So when he gave the Gettysburg Address, he’s got everybody. When he gives the inaugural, he has many, many more people. And yet the most important thing you want to carry is the meaning of the words.

Did George Washington have a southern accent? We don’t know. Does he have an English accent? We don’t know. When Vivien Leigh played Scarlett O’Hara, it wasn’t a big stretch to go from an English accent to a southern accent because that’s the sort of aristocracy of linguistics there, right?

“The Revolutionary War is the story of us, right? It’s the story of a divided America — always has been. In some ways our revolution is more of a civil war than our Civil War was.” — Ken Burns

You’ve been making films for the last 54 years. You’ve worked with some of the best actors alive during that time. Hundreds of them. In hindsight, have you ever sought an actor who was a disastrous choice for a role you wanted them to play? Did William Shatner or Christopher Walken or Joe Pesci ever step up to the microphone —

It’s funny, I just wrote down Christopher Walken. He’s got such a great voice. He’s amazing. I met him years and years ago. But yes, there have been a few people, who will remain completely nameless, who just couldn’t get it. They didn’t know how to do that voice. They’re either chewing up the scenery or projecting too much. Whatever it might be. I blame myself for it not working out. And some of them were really, really famous actors. Really good actors. Well known and respected. It didn’t work out (laughing).

I read that after your latest promotional tour for “The American Revolution,” you speculated that of the 340 or so million podcasts floating around, you’ve sat down for half of them to discuss this film.

I’ve never actually listened to any of them. So I don’t really know what the effect is. I’m always assured by a publicist that this or that podcast has millions of listeners or whatever it is, but I always end up feeling like maybe I’m talking to the person and two or three people end up listening to them. It’s just a lot of conversions. Not that many films of mine ago, there weren’t any podcasts we did, right? Maybe one or two.

Has there ever been a dream project for you that just wasn’t tenable to pursue?

I don’t think so. I’ve never started a project really in earnest and had to abandon it. There are always challenges to any project obviously. But we’ve made all the films that we’ve started to make.

Further viewing from Ken Burns:

- “The Civil War” (PBS, 1990)

- “Baseball” (PBS, 1994)

- “Jazz” (PBS, 2001)

- “Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson” (PBS, 2004)

- “Prohibition” (PBS, 2011)