How to make sense of ICE arrest data

An earlier version of this post about ICE arrest data first appeared on Austin Kocher’s Substack page. We’ve lightly edited it for style and republished it here with his permission.

From Day 1 of the Trump administration until June 10, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement made a total of 95,629 administrative arrests, according to the latest data released by the Deportation Data Project. While this number is roughly on par with reports from CBS News’ Camilo Montoya-Galvez, it is well below the claim by U.S. Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem back in April that the administration had arrested over 150,000 immigrants. Moreover, the daily arrest totals have only barely begun crossing the 1,000-per-day mark, below the target set months ago; despite this, the Trump administration is now demanding that ICE arrest 3,000 people per day instead.

Which numbers are correct? How do we put these numbers in context? Is ICE meeting the administration’s enforcement expectations? What do we know about who is getting arrested?

Data is key to answering each of these questions. While some news outlets and think tanks are rushing this data into headlines, I am taking a different approach. My goal is to walk you through the process of making sense of this data so that you are prepared to make sense of the data for yourself. Whether you’re a reporter, student, researcher, writer, Capitol Hill staffer or just a curious and concerned citizen, stick around as we talk about ICE arrest data. I’ll answer the questions outlined above — and many more.

Take note: While federal government websites, documents, personnel and press releases sometimes use the terms “alien” or “illegal alien,” the Associated Press says news stories should not use the term “alien” and advises that they use “illegal” only to describe an action, not a person.

The ICE enforcement data used here was made available through the excellent work of David Hausman, professor at UC Berkeley Law, and his team — including Amber Qureshi — at the Deportation Data Project. I had the good fortune to speak on two panels together with David Hausman this spring, the first at the Ohio State University’s Emerging Immigration Scholars Conference hosted by César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández and the second at the Transparency Convening in Washington, D.C., hosted by Muckrock and others.

LIVE: New ICE Arrest Data Explained by Austin Kocher

Thank you to everyone who tuned in today to learn about the new ICE arrest data released by the Deportation Data Project.

Read on SubstackIt is exciting to me that we now have a team in the immigration world who is fighting to get immigration data and make it publicly available rather than shuttering it away behind paywalls or letting it languish unused on computers. It means that we have an opportunity to level up our shared knowledge and increase our collective ability to hold administrations — all administrations, Republican and Democrat — accountable for their immigration enforcement policies and practices.

Understanding ICE ERO administrative arrests

The news media and policy analysis worlds operate on an aggressive publishing timeline that would make academics’ heads spin. But what academics lack in speed, we try to make up for in thoroughness. That’s why we are starting with the basics.

The data under discussion represent administrative arrests by ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO). Therefore, we need to answer two questions:

- What is an administrative arrest?

- What is ERO?

What is an administrative arrest?

Let’s begin with known descriptions of ICE’s administrative arrests. The Office of Homeland Security Statistics (OHSS) defines an administrative arrest as “Detaining by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) within the interior of the United States of an alien unlawfully present in the United States or of a lawfully present aliens (sic) who is subject to removal.”

An ICE report from 2018 defines an administrative arrest as “the arrest of an alien for a civil violation of U.S. immigration laws, which is subsequently adjudicated by an immigration judge or through other administrative processes.”

Since it is relevant for this discussion, a 2023 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report also describes the connection between an administrative warrant and an administrative arrest as follows: “ICE administrative arrests are based on administrative arrest warrants. Unlike judicial warrants, ICE warrants are purely administrative, as they are neither reviewed nor issued by a judge or magistrate, and therefore do not confer the same authority as judicially approved arrest warrants.”

Let’s boil this down to the simplest definition: An administrative arrest is an arrest for a civil violation of U.S. immigration laws. These are not criminal arrests, even if the person arrested has a criminal history.

But wait: Can ICE make arrests without an immigration warrant and can ICE make arrests for criminal violations? Under certain conditions, yes and yes. A recent Congressional Research Service (CRS) report, updated in June 2025, describes the following conditions under which ICE may make an immigration arrest without a warrant:

“1. the alien, in the presence or view of the immigration officer, is entering or attempting to enter the United States unlawfully; or

2. the immigration officer has ‘reason to believe’ that the alien is in the United States unlawfully and is likely to escape before a warrant can be obtained.”

Since ICE usually does not conduct border enforcement directly, the first one is less likely of a scenario. However, the second point here is crucial, since it implies that as long as an ICE officer says, “Hey, I thought this guy was an illegal [alien] and he was going to get away,” ICE could conduct an administrative arrest against lots of people.

I’m not splitting hairs here. The reason this matters is because when we are writing about administrative arrest data, we should be aware that while these arrests should be accompanied by warrants, there are loopholes. Some percentage of all ICE administrative arrests will have a warrant and some percentage will not. And this administration has an incentive to ignore even the low bar of ensuring that everyone has an administrative warrant.

The CRS report also describes the circumstances under which an ICE officer may make a criminal (rather than administrative) arrest: “Section 1357(a)(4)-(5) permits designated immigration enforcement officers authorized under regulations to make warrantless arrests of aliens and other persons for criminal offenses in specified circumstances (e.g., when the offense is committed in the officer’s presence, or the officer has reason to believe the suspect committed a felony and would likely escape before a warrant could be obtained) during the course of their immigration enforcement duties.”

In short, ICE officers, like most law enforcement officers, generally have the authority to arrest someone for a crime committed, or about to be committed, in front of them.

How does this affect our analysis? It means that if we are looking at ICE administrative arrest data, this data likely does not include any additional arrests that are not administrative arrests. That is, although this data shows 95,629 administrative arrests, ICE might have conducted criminal arrests that are not included here.

In summary: Don’t assume that administrative arrests constitute the entire universe of ICE arrests and don’t assume that all administrative arrests were conducted with an administrative warrant. This administrative arrest data is simply that: administrative arrest data. When writing about this data, be careful not to embellish with assumptions that are not legally or empirically verified.

What is ERO?

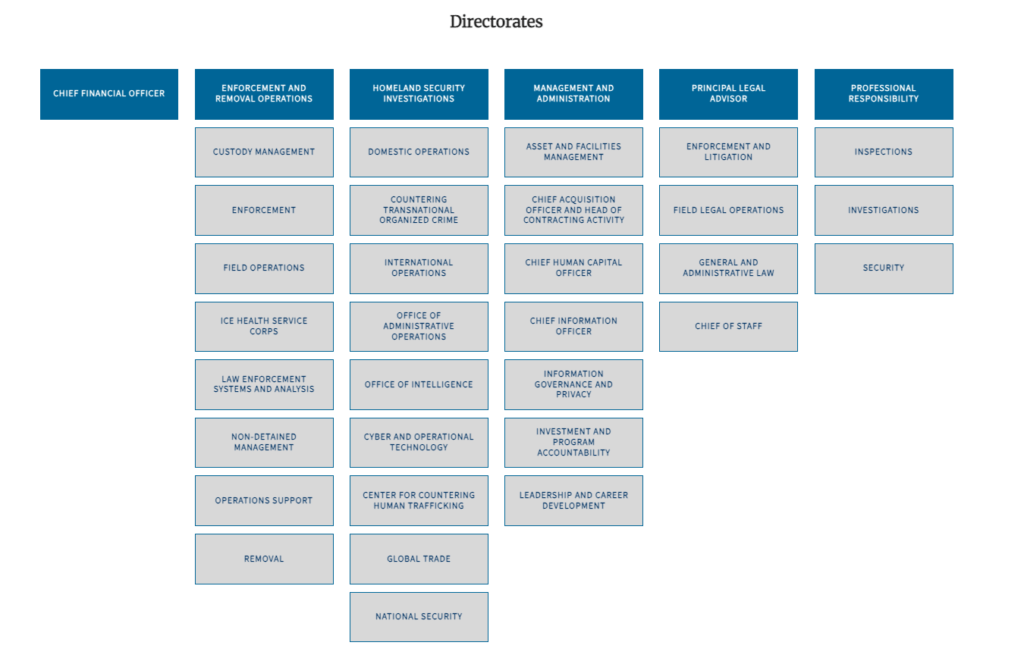

ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) is not the only division within ICE, but it is the division that most of the public imagine “ICE” to be. ERO runs the detention centers, conducts enforcement actions, arrests people, effectuates deportations — and so on. The Office of Principle Legal Advisor (OPLA) oversees the attorneys that represent ICE in immigration court.

Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) is sort of like ICE’s version of the FBI. They conduct more complex, sophisticated and wide-ranging law enforcement activities. HSI has long felt out of place within ICE, so much so that they have tried to distance themselves from ICE due to its controversial role in politics — even going so far as to seek a home outside of ICE entirely.

The organizational structure of ICE is important for our analysis here, because when we are looking at “ICE ERO administrative arrests,” we are only looking at ERO. HSI also has the authority to make administrative and criminal arrests — but since this is not HSI data, we should assume that the data does not include HSI arrests. As with my earlier point, this reinforces the observation that the current dataset does not necessarily include all arrests made by ICE. I think it goes without saying that the data also does not include arrests by Customs and Border Protection (CBP), including Border Patrol.

There is one more reason why this section is so important. The Trump administration has made a flurry of unverified claims about arrests, criminality, deportations and much more. However, the administration is incredibly sloppy in actually saying what they are counting, which means that attempts to “fact check” the administration are difficult not only because we don’t always have the data, but because the administration itself is so nontransparent about its own methodology. As a result, sometimes the administration appears to be outright lying when in fact they are engaging in some funny math or counting things in nonstandard ways that might be plausible (if contestable). Other times the administration’s overall narrative and political rhetoric is demonstrably unfounded. And underlying all this is the fact that so few people, reporters and researchers included, take the time to patiently and precisely march through the data in a way that ensures clarity and accuracy. Hopefully this series of posts will help with that.

Validation

Now that we understand the nature of this data, let’s discuss validation. The first step to using any administrative dataset is to validate it, which means making sure that the data accurately represents what it claims to represent. I like to summarize validation approaches as internal and external. Internal validation means assessing the dataset to check for logical consistency, appropriate headings, correct data formats, etc. External validation means checking the dataset’s numbers against other known sources of data for overall consistency and accuracy.

For example, although the Deportation Data Project is not really designed to conduct in-depth analysis itself, they did flag that their recent removals data has some issues. Again, this only becomes evident through careful validation.

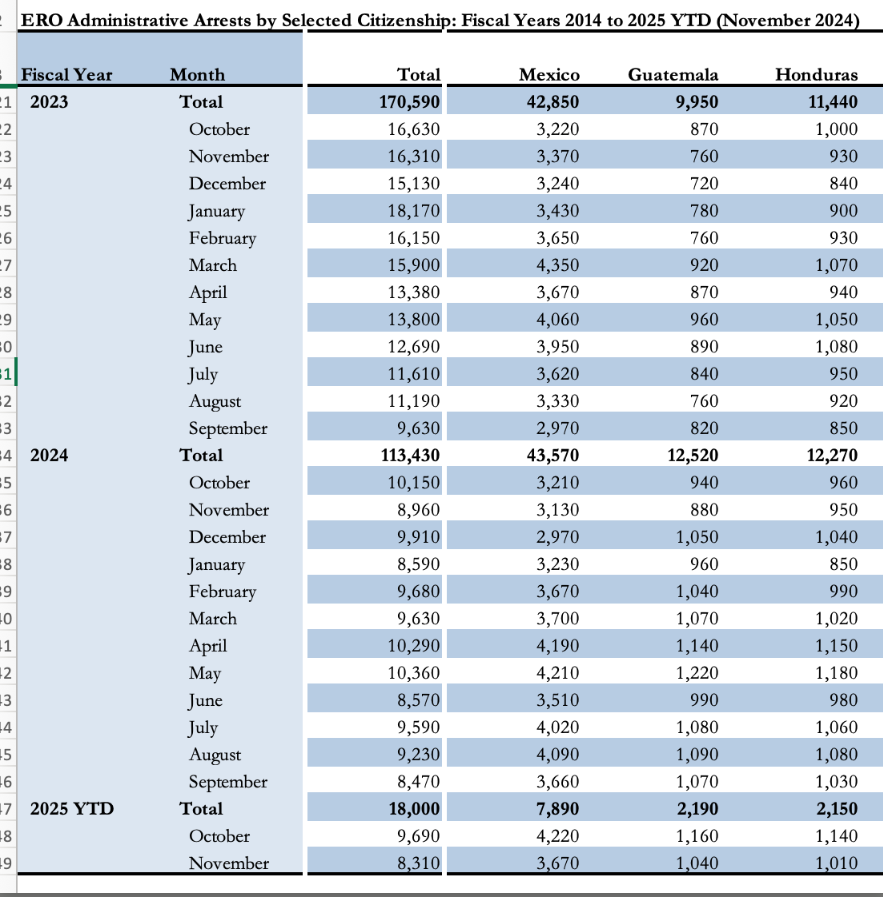

For the ICE ERO administrative arrest data, I aggregated the monthly totals from the Deportation Data Project’s FOIA and compared those to the data previously released by OHSS (before the Trump administration sadly squashed their work). The most recent OHSS monthly enforcement data was published in January 2025 and provides data through November 2024.

Although there are more sophisticated ways of measuring the consistency of the data, keep in mind that data pulled from a transactional government database at different times will always contain some incongruities as data changes over time. Thus, a simple visual analysis is fairly sufficient to determine reliability. See the graph below that shows the monthly consistency. At least we can say that whatever OHSS published is consistent with what the Deportation Data Project received, which implies that if both are wrong then something much more concerning is at play.

Note that validation is not a one-time thing. It is important to approach this work with the mindset of a scientist. Check findings and conclusions against other known sources, questions your assumptions, show your findings to other experts to get feedback. Most importantly: beware of “motivated reasoning.” Although we should approach datasets with real-world questions, avoid assuming that the data supports your pre-made interpretation or aligns with your values. Let data surprise you — that’s half the fun.

Below is the screenshot from the OHSS data. Once you learn to decode the specific wording to the titles of various datasets, you’ll start to recognize and properly interpret the various data sources within DHS. Note that since OHSS also provides breakdowns by major nationalities, I could have gone a step further to validate the monthly arrest totals by nationality, as well (and I might do that if I do a deep dive into the nationalities).

Next steps

Now that we have discussed the context for this data and validated it, the next step is to do some initial analysis with an eye for the questions I raised above as well as a specific complaint I raised during the first week of the Trump administration: ICE’s posting of unverified arrest data online. In a post at the time, I raised concerns about the agency’s ability to produce accurate arrest data on a daily basis and post it online. (See that article below.) The administration stopped doing this after arrest numbers appeared to fall, but until now we never had a way to check their claims. Now we do.

Related reading:

“ICE’s Immigration Enforcement Data: Can You Trust It?”: In early February, Kocher published this essay about data skepticism and a call for greater transparency.

“ICE Set to Arrest a Record 35,000 Immigrants in June; Daily Quotas are Political, Not Practical”: In Part 2 of his series on ICE arrest data made public by the Deportation Data Project, Kocher examines daily and monthly arrest totals.

The post How to make sense of ICE arrest data appeared first on The Journalist’s Resource.