Here Today, Gone Tomorrow.

This post is about an evergreen but newly urgent topic: How mainstream media in general, and the New York Times in particular, ‘frame’ the political news. Especially in their use of headlines and subheads—hed and dek, in the lingo of the trade, plus ‘social sell’ online—which reach vastly more readers than the nuanced contents of the stories themselves. These framing decisions matter at the Times, which is the single most influential English-language news source and tone-setter.

Here’s the twist in today’s installment: We’ll start with encouraging examples of recent Times framing. And then ask, Why not more of the same?

Let’s go back in time two full days, all the way to Saturday morning, December 6, 2025.

Telling it straight: Story play two days ago.

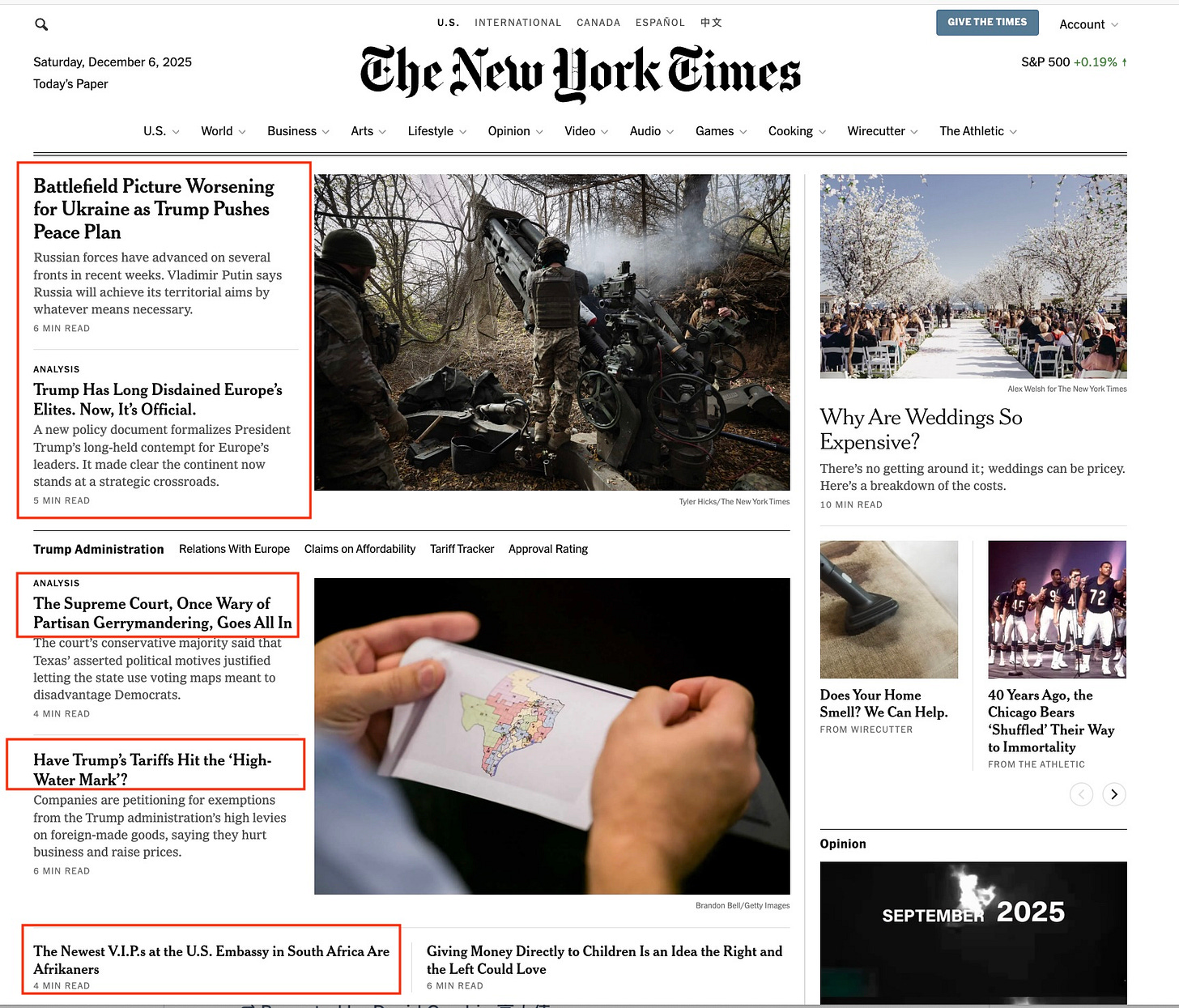

Here is Page A1 of the print NYT this past Saturday, with red highlights by me:

And here is the digital front page online, as I saw it that same morning:

Within the media business, a print front page is still an important signaling device. The editors are saying: This news matters. This big project is one we hope you pay attention to.

The comparisons and contrasts between the print and online presentations illustrate the different roles modern media companies balance. The print version is more august: We are still the newspaper of record. This is our “first rough draft of history.” For last Saturday’s paper, this meant a front page leading with an obviously long-planned obit for a history-making architect; a story about a potentially historic Supreme Court case; and a remarkable piece of investigative reportage about a lurch away from the modern history of public health.1

The online version is closer to the “first rough draft of now.” It also uses its space to steer readers to coverage of parts of life other than hard news.2

But despite those differences, what caught my eye in both versions was how clear and declarative the Times’s presentation is. RFK Jr “is upending” vaccine science. (Not “critics say…”) The GOP Supreme court “goes all in” on partisan gerrymandering. (Not “some observers contend…”) The paper is announcing, in forthright terms, what its reporters and analysts have learned.

And it wasn’t just these front pages.

The same declarative tone ran through many other hed-and-dek presentations in that Saturday paper, both print and online. For instance:

A story about Trump-era policy toward Europe:

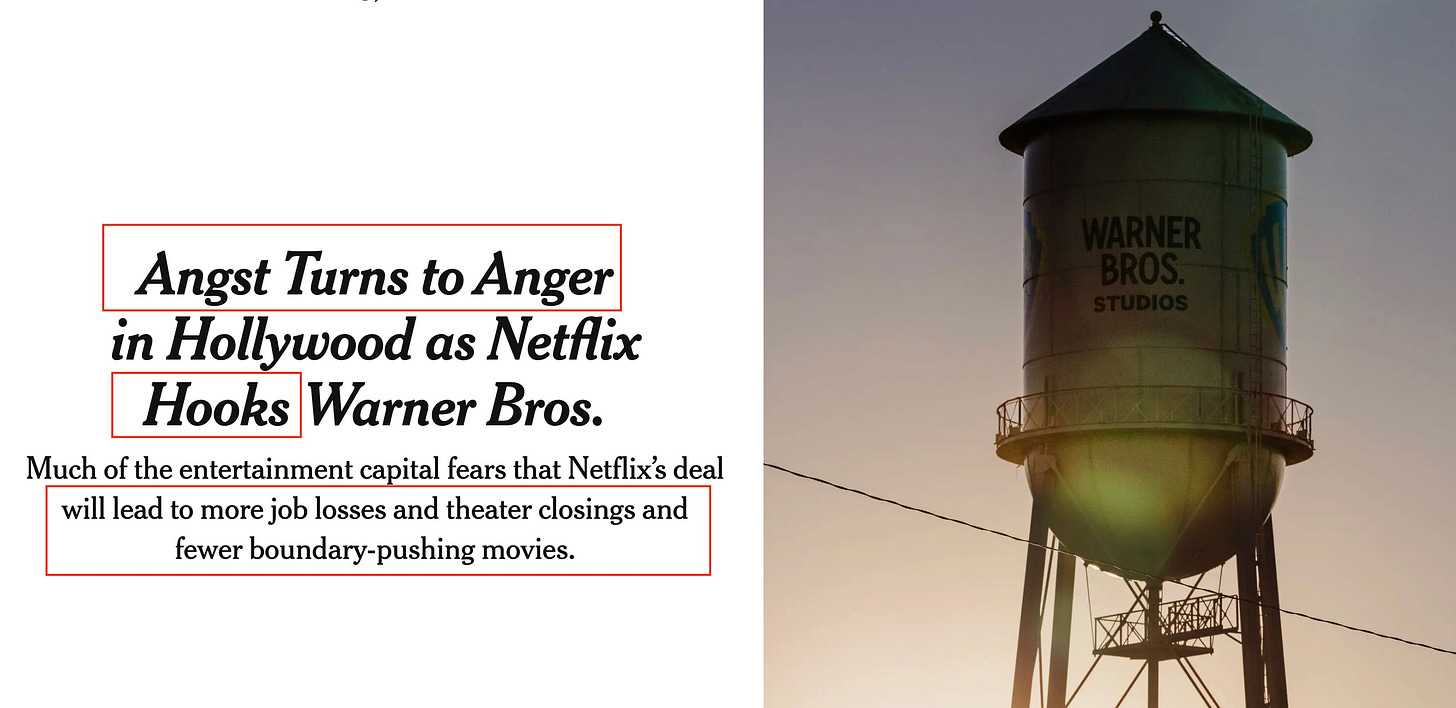

This online presentation of the Netflix/Warner saga, which was later in the print paper:

And from a few days earlier but still up on the site on Saturday, a very plainly phrased item in the online Politics page:

There were a lot more examples through Saturday’s paper, both print and online. The point about the framing in all these stories is that the presentations matched what the reporters had found. The editors weren’t worried about being seen as taking “sides.” They were on the side of their reporters, and the truth.

Telling it crooked: Story play today.

Everyone who has criticized the NYT for story framing (for instance, Margaret Sullivan, Jay Rosen, Mark Jacob, the author of NYT Pitchbot, and others), has called out the difference between its presentation of US politics and its treatment of nearly everything else.

To wit: In coverage of tech, business, science, and so on, the paper tries hard in its presentation to distill what its reporters have found. But when it comes to US politics, whoever in charge often seems subject to a sixth-sense fear that someone will say the coverage is “biased.” (Which of course the right-wing media will say, whatever the paper puts out.)

There’s no starker illustration than a headline on this morning’s print front page.

The online version of the headline was similar: “One Step From Citizenship, Some Find It Eludes Their Grasp.”

“Proves Elusive”? “Eludes Their Grasp”? Seriously? What must the reporters have thought?

If you read the story, you’ll see that it conveys nothing like the “mysterious misfortune” tone of those headlines. It’s a detailed and, to me, heartbreaking account of intentional cruelty. It describes immigrants who have gone through the years-long, ever-stricter process of qualifying for US citizenship, only to have that prospect ripped away at the last moment.

Because of new Trump crackdowns on immigrants from “bad” countries, people who are just days from their swearing-in ceremony, and in some cases have even arrived at a courthouse to take part, are told that it’s been called off. Most Americans who have witnessed these ceremonies find them unforgettably emotional, and a powerful source of national pride. We have now instead an example of casual heartlessness, from people in command.

All of that drama and chain of causation is in the story. What’s in the headline—again, all that most readers will ever see—boils down to, “darn the bad luck.”

Why not something closer to the truth, which would fit the same line count for a headline? Something like:

“Trump Policy / Blocks Last Step / To Citizenship.”

or

“One Final Step / To Citizenship / Now Blocked.”

Maybe if the story had been in last Saturday’s paper, it would have gotten that kind of play? Who knows why editors played these stories one way, versus another — which brings me to the final point.

Who makes these calls, and why?

The crucial theme connecting these examples is not that the Saturday stories were “anti-Trump,” as Karoline Leavitt or Stephen Miller might say. Rather the point about whole collection of stories is that in Saturday’s paper, the presentation lined up fully behind the reporters’ findings. But by Monday, the mute-pedal was applied.

I can’t be the only one to wonder: Why? How? By whom? Signifying what? Someone new on the desk on Saturday? A conscious shift in direction? Just coincidence that day?