Freedom of the Press Isn’t Just a Legal Issue

Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (often its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

From the beginning of this presidency, I have urged us all, pace Nixon henchman John Mitchell, to “watch what they do, not what they say.” I think that’s important to shaping our coverage generally, and to making sure editors rather than government officials are setting the news agenda.

Libel humbug and Pentagon oppression

In charting Trump’s attacks on the press, I think this approach has been helpful to those who have demonstrated the restraint to follow it. In the early months, the most significant thing actually done in this arena, in my view, was the limitation on White House access for the Associated Press after they refused to toady to Trump’s childish insistence on “renaming” the Gulf of Mexico. I was critical of the failure to take collective action against this, and remain so.

More recently, I’m much less worried about the huffing and puffing of frivolous libel suits, whether against the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal. Trump has now become the first, second and third sitting president to sue the press for libel, and he will soon be 0-3 in these cases, with the summary dismissal of the most recent case against the Times actually quite humiliating for the private lawyers who sloppily presented it. Claiming $15 billion in damages didn’t fly—maybe next he’ll try a trillion (you too can sue anybody for any amount you can imagine!).

I’m much more concerned about the new policy announced for coverage of the Pentagon, the original details of which are here, with an excerpt from a revised version here. Some of the policy is petty and unwise—restricting reporters from certain areas where they have long been permitted. But other provisions are much worse than that. In particular, the policy seeks to force reporters who want to be able to set foot in the nation’s largest public building to abstain from publishing not only any classified information, but also any non-classified information that the government hasn’t approved in advance. (Based on the published excerpt, I think a New York Times report is far too sanguine about the revisions.)

In other words, even if information isn’t sensitive enough to qualify as an official secret, Pete Hegseth, no master of information handling, wants to be able to choke off its circulation. Using social media to encourage people generally to disclose unclassified information, for instance, is ostensibly prohibited. That is to say, the policy seeks to effectively end independent journalism emanating from an office building paid for and maintained by taxpayers at a cost of billions.

Such a policy is impractical—most of the publication of classified information occurs when the government decides to leak it, and this would make that somewhat harder to effect. It is also offensive— denying the role of a free press in our system. And, if actually successful, it would be self-defeating—just like in authoritarian countries the world over, people would quickly learn not to believe anything bearing a Pentagon dateline. The implementation of the policy was delayed, perhaps as cooler heads than Hegseth’s (a large proportion) weighed in, but the revised version, while offering a lengthier rationale, would have been recognized as deeply offensive if initially proposed.

The crucial importance of right and wrong

The policy may also be illegal (and the newer version certainly misstates the law on the disclosure of unclassified information), but that seems to me far from the most important thing about it. Yet, legal questions have been at the heart of the organized press response to the policy so far.

I think that is a mistake, and this is the most important point I want to make this week.

The AP White House ban can serve as a case in point. That was also petty, vindictive and wrong. The President doesn’t get to decide on a newsroom’s stylebook, and he shouldn’t get to punish stylebook choices he doesn’t like. Imagine if some future president, for instance, banned from White House press pools any news organization that didn’t publish pronouns as part of its bylines. That is just like what Trump has done with AP.

It is neither necessary to cite a legal case nor to bring a legal action to know that this sort of speech policing is anathema to the freedom of speech and of the press that almost all Americans value highly. And that is why I continue to think that the rest of the White House press corps should have refused to go places from which AP was banned. It is a sorry statement that our nation’s TV comics have shown more solidarity in the face of Trump’s censorship than have its leading newspapers.

Instead, we have cast these moral and philosophical questions as legal ones, depending on the intricacies of complex legal doctrines such as those governing the use of “public forums.” In the AP case, that produced an early victory, but then a later defeat as Trump altered the facts on the ground to his benefit.

The most important point—the point which needs not to be lost—is not whether Trump has the legal right to limit press freedom, but whether he is right in doing so. He is not. This is ultimately an ethical question, and a political one.

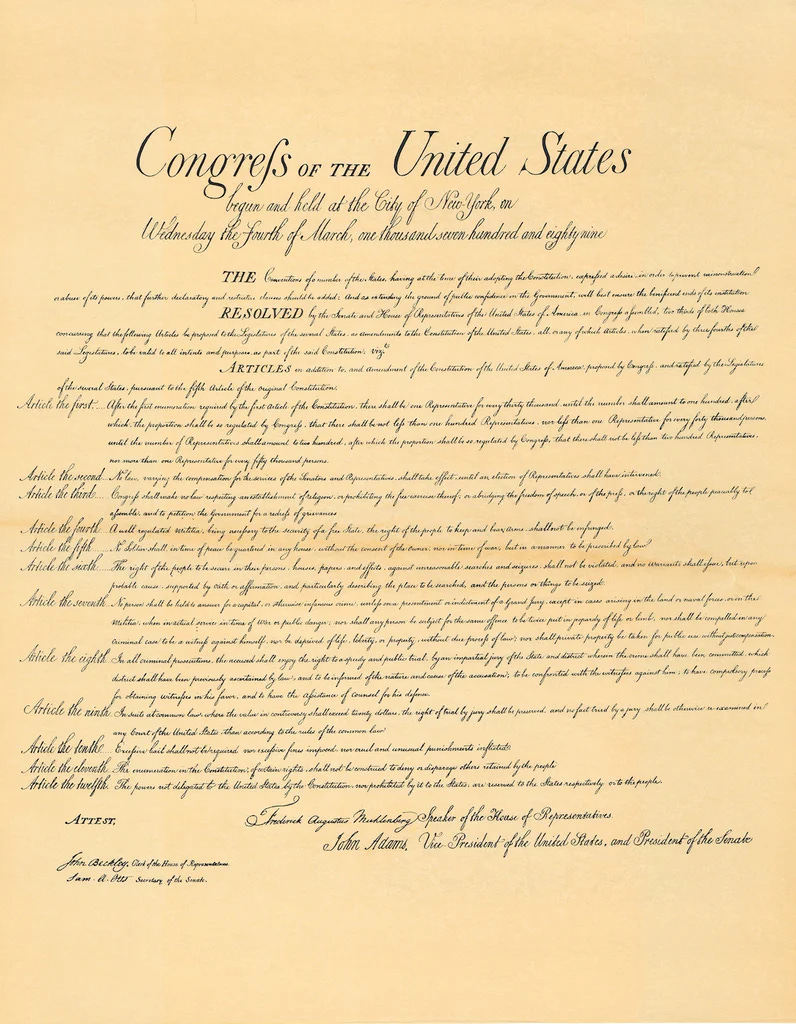

The courts are a critical redoubt of our freedoms, but they are not our most important defense. That, instead, is the support of the American people for our shared liberties, for the Constitutional values that undergird particular holdings of constitutional law. We shall, in the next few years, nobly save or meanly lose press freedom in this country, depending on our ability to convince our fellow citizens to hold fast to it. That, in turn, will require an appeal to the rightness of our cause, not alone to the arguments of lawyers.

Thanks for reading Second Rough Draft! Subscribe for free.