50 years of advocacy and impact: Celebrating NABJ’s enduring legacy

As the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) prepares to celebrate its 50th anniversary this December, the organization stands as a powerful testament to the legacy of its founders and the resilience of generations of Black journalists who followed in their footsteps.

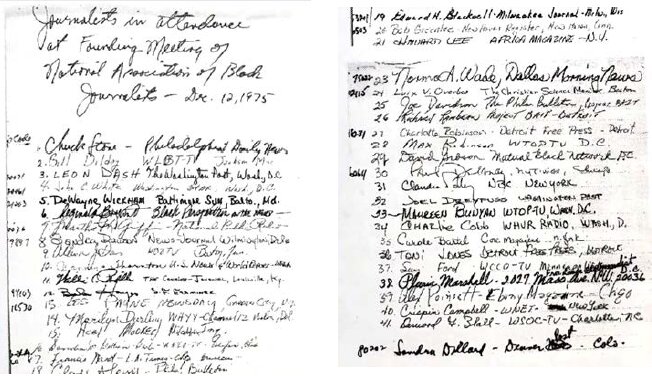

From its inception on Dec. 12, 1975, in Washington, D.C., NABJ has grown from 44 founders to more than 4,000 members nationwide. Its mission has always been to increase Black representation in media and to hold newsrooms accountable for how they report on Black communities. That mission was born in the wake of the 1968 Kerner Commission Report, which exposed how mainstream media disenfranchised Black journalists, perpetuated harmful stereotypes and ignored systemic racism.

One of the pivotal figures in that founding meeting was Chuck Stone, the first Black columnist for the Philadelphia Daily News, who helped draft NABJ’s original mission. Stone, a Tuskegee Airman and civil rights advocate, was honored this year with a posthumous Pulitzer Prize Special Citation, recognizing his lifelong dedication to justice and elevating underrepresented voices. His leadership helped set NABJ’s tone of decades of advocacy.

“It was hostile in many newsrooms back then,” recalled Joel Dreyfuss, a founding member of NABJ. “There was mistrust. They thought we saw the world differently — that we were activists and there would be disagreements over how stories were told.”

What started as informal meetups between Black journalists, who were assigned to cover civil rights events or stories of interest to Black readers, evolved into regional associations. Philadelphia, Boston, New York and Los Angeles had local associations that Black journalists could turn to for advice or support if they faced discrimination or retaliation for speaking up about biased coverage. Stone led the Philadelphia chapter.

Dreyfuss, who began his career as a reporter for The Associated Press in New York and later worked for major dailies and national publications, said that, despite the Kerner Report and discussions about improving newsroom diversity, early efforts fell short — leaving Black reporters isolated and vulnerable. “Most papers had no Black reporters at all — or maybe just one or two. Not exactly great representation.”

Signatures for the journalists who attended the founding meeting of the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) on Dec. 12, 1975 (Photo: Courtesy of NABJ)

The push for a national organization grew into a movement at the persistence of Stone, who organized a meet-up in Washington, D.C., by journalists sent there to cover a national meeting of Black politicians. Some 70 to 80 people attended, recalled Allison Davis, a founder and the organization’s first parliamentarian.

“There was some fear at the time about possible pushback from employers, but we got 44 to sign on,” said Davis, who was, at 25, the first Black producer at WBZ-TV in Boston and who went on to become a producer at NBC News. “We were able to get the officers named at that first meeting. Chuck was just brilliant. He ensured this organization would not only exist but thrive.”

A year later, the group had its first convention in Houston, Texas, and Stone was elected as the first NABJ president. Davis helped draft the constitution, which was voted on, setting the organization’s priorities and working structure.

Joe Davidson, NABJ founder and columnist for The Washington Post (Photo credit: Sharon Farmer)

Washington Post Columnist Joe Davidson, a founder working in Philadelphia then, said Stone recruited him to organize the first two conventions. He explained the scope of work was multi-pronged: “One of the things we talked about was improving coverage of the Black community, and so that’s been a point of NABJ from the very beginning,” Davidson said. “We talked about getting more Black journalists into news organizations, getting more Black journalists into the upper echelons of news organizations, strengthening the ties between Black journalists and mainstream media and Black journalists and Black-owned media. So, improving coverage was definitely a main motivation behind NABJ.”

Those priorities remain active for the organization 50 years later.

Editor & Publisher reported on the organization’s founding in an article in January of 1976 and noted in its coverage that seven of the 15 board members were women. It quoted Stone as saying:

This photo of the NABJ founders was taken at the NABJ 2023 convention in Birmingham, Alabama. (Photo credit: NABJ)

“Our formation is mandated by the fact that we are probably the last group of Black professionals to organize nationally. On the eve of this multi-ethnic society’s 200th birthday, it is fitting that such an organization comes into existence. As professional journalists, we are inextricably wedded to the First Amendment. As Black Americans, we are as deeply committed to First Employment.”

Dreyfuss explained that NABJ helped alter the racial makeup of American newsrooms and changed how news organizations cover communities of color. “That’s an achievement — to have grown and lasted this long,” Dreyfuss said. “They did change the makeup of the newsroom. We affected the coverage and made more people of color players in events that are covered.”

Joe Davidson emphasized the emotional and professional sustenance the organization continues to provide. “It became a place of rejuvenation,” he said. “We would go to these conferences every year and leave really feeling energized.” He recalled the ongoing relevance of panels like “How to Cope in the Newsroom,” which provided a safe space for Black journalists to share the challenges of navigating predominantly white newsrooms.

“But one of the things I don’t think we mention enough is the family feeling you feel at NABJ,” Davidson added. “Folks go there, and they’re just so happy to see people from around the country. It honestly is a warm family feeling at those conventions. I think that’s why people keep coming back.”

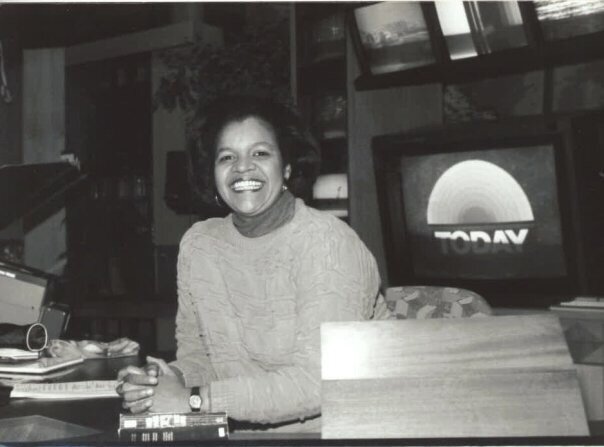

Allison Davis, NABJ founder and the organization’s first parliamentarian

Central to NABJ’s mission is a commitment to fostering young journalists through mentorship and training. Davis said one of the organization’s hallmark programs is the Student Multimedia Project, which brings college students nationwide into a fully operational newsroom during the annual NABJ Convention. Participants work under the guidance of seasoned journalists and public relations professionals to produce TV newscasts, newspapers, multimedia packages and corporate communications.

“Nobody had seen something in me like these people see in me,” said Akayla Gardner, who joined the Student Project in 2020. “The last day of the convention, I was crying because I hadn’t had people like that who were willing to come alongside me as a journalist and support me in that way. It was really special to me.” Now a White House correspondent for Bloomberg News at just 26, Gardner credits the experience and her mentors, including Davis, with transforming her sense of possibility. “I definitely began seeing myself differently as a journalist based on what they saw in me. It was really transformational for me.”

DeWayne Wickham, NABJ founder and dean emeritus of Morgan State University’s School of Global Journalism and Communication, said the organization remains crucial in today’s fraught media and political environment. “NABJ has made a difference in the number of Black journalists who are on the front lines of reporting and producing journalism in this country,” he said. “The attacks on journalists today are very similar to the ones we saw 50 years ago. The difference is that we now have an organization willing to stand up and speak out.”

Over the decades, NABJ — like most journalism associations — has faced its share of challenges. At times, disagreements have emerged over the organization’s priorities and direction. Financial strains have tested its resilience.

Last year’s convention drew headlines when then-candidate Donald Trump agreed to attend the event for a Q&A with journalists. Some members believed having President Trump on stage was an error, citing his propensity for lying and his mistreatment of Black women journalists. Others argued it aligned with NABJ’s tradition of putting newsmakers and political candidates before journalists’ questions. The arguments played out on social media throughout the convention. “We have disagreements. In the end, it didn’t divide us,” said Wickham. “We debated it — strong in our opinions — and came away as one.”

Allison Davis was, at 25, the first Black producer at WBZ-TV in Boston and who went on to become a producer at NBC News. (Photo credit: Courtesy of NBC)

In May the organization announced a leadership transition. Drew Berry, who served as the nonprofit’s executive director for nine years, announced his retirement. Davis said in a statement, “Drew Berry leads with a deep commitment to our mission. Under his leadership, NABJ has grown stronger — not just in numbers, but in influence and impact.” As of publication, a replacement had not been named.

Just recently, Journal-isms’ Richard Prince reported that current president, Ken Lemon, would face challengers in the leadership election during this year’s conference. Prince reported that Errin Hayes, editor-at-large of The 19th, and Dion Rabouin, founder of The Black Press and former Wall Street Journal reporter, filed paperwork to run for president of the organization — citing desires to advance the institution for a new era.

On Feb. 16, 1978, the NABJ board members and Black publishers were invited to the White House to meet with President Jimmy Carter. The all-day briefing also included the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Patricia Roberts Harris. (Photo credit: The White House)

This year’s convention will be held in August in Cleveland, Ohio, and a special ceremony will honor the founders. NABJ also has a documentary about the organization’s history and impact with Storyboard Films, headed by James Blue. The film will be screening at film festivals this summer.

The founders E&P spoke with said NABJ’s work remains critical today as newsrooms shrink and economic and political pressures intensify. Black journalists often find themselves disproportionately affected by layoffs and editorial marginalization, said Dreyfuss. “Most papers plodded along without making much change over the years. Some are showing that their commitment to diversity is shallow. We are in a trough now, and things are moving backward.”

Still, despite frustrations and systemic setbacks, Wickham believes the sense of collective support — present since that first meeting — will allow NABJ to endure. “There’s something about this spine of consciousness that helps us weather and keeps us rising. We grow together.”

Davidson echoed that sentiment, describing NABJ’s enduring strength as rooted in a shared sense of purpose and belonging. “The sense of community is invaluable professionally and personally,” he said. “It’s not necessarily something you’ll know if you just look at hard metrics. But for me, it’s that sense of community and family that really is crucial.”

Half a century later, that founding spirit continues to shape the next generation of reporters, editors and storytellers — still fighting for equity and pushing journalism forward. Dreyfuss said, “To be at that first meeting with just 44 of us and now go to a convention with 3,000 people is a legacy. That’s hope.”

Diane Sylvester is an award-winning 30-year multimedia news veteran. She works as a reporter, editor and newsroom strategist. She can be reached at diane.povcreative@gmail.com

Diane Sylvester is an award-winning 30-year multimedia news veteran. She works as a reporter, editor and newsroom strategist. She can be reached at diane.povcreative@gmail.com